I, Too

In the Age of American Fascism

Besides,

They’ll see how beautiful I am

And be ashamed—

I, too, am America ~Langston Hughes

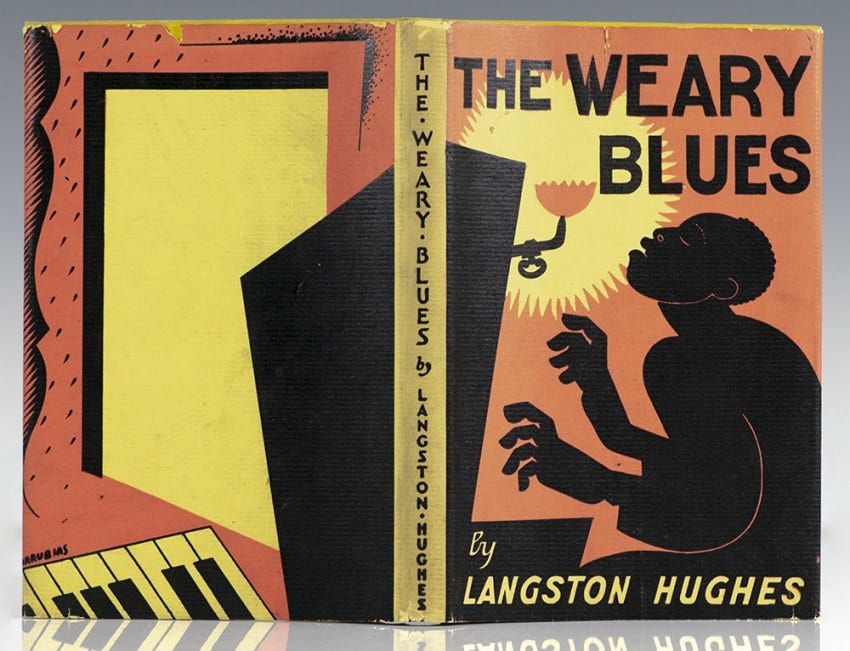

In 1926, when Langston Hughes penned the poem “I, Too” fascism waif through the air like the smell of baked cannoli on the streets of Rome. Benito Mussolini had come to power in 1922. The young Langston witnessed Mussolini’s solidification of power over Italy as he wandered his way around parts of Africa and Europe as an adventurous young sailor in 1924. Hughes vagabond his way through Desenzano del Garda, Verona, Venice and finally Genoa looking for work alongside local Italians and immigrant workers before he could find another ship to return back to the United States.

Over his stay in Italy, he heard Mussolini’s fascist speeches and saw his Ice-like Black Shirts rousting the poor, the underemployed and immigrants in order to make Italy’s economic dislocation appear somehow better than it was in reality. Italy, however, was even more impoverished than had been throughout the 19th century. The catastrophic aftermath of WWI had left the country crippled. And Mussolini tapped into the resentment Italian’s felt. In Mussolini’s mind Italian dislocation was not about a terribly administered government, but the fault of others who violated the purity of Rome’s glorious past.

Italian fascist rhetoric was eerily reminiscent of Southern Democrats after the American Civil War, who used the populist narrative of the Lost Cause rhetorically arguing it was the nobility of the Confederacy that was at stake in the South not enslavement. It was white Southern culture that was wronged by Northern aggression, not the unfree laborers for life or the propertyless who earned an oligarchical elite billions harvesting and picking cotton for international markets. In an attempt to destroy the limited political gains that Black Americans had made after the Civil War elite Southerners chose to “redeem” the South by redefining the national narrative of losers as winners and commandeering some of its most important institutional apparatuses like the military using white supremacy as an identity politics.

In Italy, authoritarian rhetoric was not driven by the long list of administrative incompetencies, but rather the other-–homosexuals, Eritreans, Jews, Roma, and low-level criminals. Governmental and religious corruption were wallpapered over by the mythological past of the Roman empire. By the time Mussolini came to power the Roman Empire had been collapsed for 500 years and literally the country was a ruin. Fascism as mouthed by El Duce (the Leader), as Mussolini called himself, appealed to the anxiousness, frustrations, impoverishment and joblessness of Italians. And Langston witnessed how alienated many Italians were and how Mussolini’s con-man rhetoric persuaded some and brutal thug like enforcement scared others to go along with the message!

Langston’s global travel enabled him to see first-hand what so many could not see up close. He saw the crisis of Italian politics unfolding and he understood from his own experience as a United States citizen how racist identity politics led to exclusionary practices in America. I am sure at the time he could not have guessed how far Italy’s exclusionary politics would go joining an alliance of hatred across Europe as Jewish populations were systematically decimated.

The young Langston, however, was not totally naive. He had lived with the pogroms occurring in Black American communities between 1908 to 1924 when he returned back to the United States such as the 1908 Springfield Massacre, 1917 East St. Louis Massacre, the 1919 Red Summer, the 1921 Tulsa Race Massacre, and the 1923 Rosewood, Florida massacre all driven by vicious populous rhetoric and newspapers that fueled social resentments that ended in untold murders of innocent men, women, and children.

The rhetoric of white heritage politics that now oozes out of the mouths like bile from public officials is troublesome. We must always pay attention to its intended violent effects. It is never meant to bring people together to fight their common dislocation it is simply to blame others. This aggrieved political rhetoric is intended to disband a collective citizenry into tribalism rather than build a nation. Resentments are easily fostered but not easily corralled. And this is a perennial problem especially when hateful propagandistic rhetoric is now enjoined by unregulated social media.

This is why I, Too is an important poem to remember in this moment. Politicians who advance history as aggrievement seek false indoctrination, not the building of a free society. Authoritarianism is a wet dream aroused by manipulating hatreds. This hate must be confronted by truth, historical accuracy, protest and self-defense.

We, as citizens, should know that the history of the United States has always been multi-heritage, mixed ethnically and unequal economically. Not everyone’s ancestor came on the Mayflower. The United States was born out of the 17th century British empire. Building upon the mother country, North America became a slaveholding society using gender, property and race to legally define societal inequalities as the British elites had done in the Caribbean. We may not like this, but that’s history. And history wherever it is derived is always a painful saga.

And history is never a happy moral tale as the 20th century theological ethicist Reinhold Niebuhr reminds us:

“One of the most pathetic aspects of human history is that every civilization expresses itself most pretentiously, compounds its partial and universal values most convincingly, and claims immortality for its finite existence at the very moment when the decay which leads to death has already begun.”

This is why we rely on poets, prophets, psalmist, and writers to advance insight to the false indoctrination that monarchs and leaders choose to use to do their unrighteous bidding.

In I, Too, Langston understood the richness of multi-heritages that made up the United States. He knew this all too well as a Black American who lived under the rawness of segregationist politics in Jim Crow America. In this poem he reminds us that the people who were once excluded will not always be ushered to the back door and the kitchen and made to feel ashamed. He understood the excluded folk—Black folk, gay folk, hillbillies, immigrants, laborers and women of every station—are the people who make America great. They, too, are American and as Americans there is nothing more American than to fight back.

Randy your post is on point. Fight back.

Very insightful and thought provoking post. Also, it was great to meet you at the AHA conference last week in Chitown!